Sophisticated Curves of Gaya Pottery

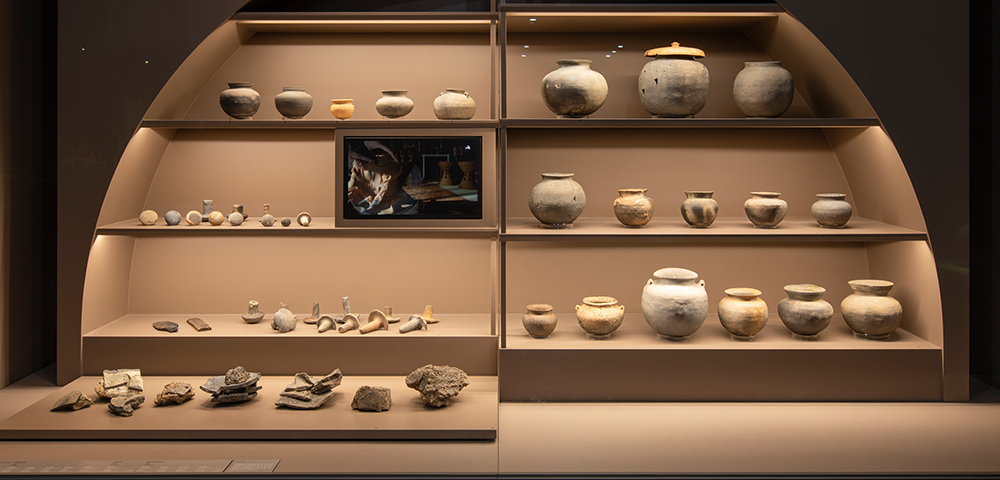

Gaya pottery consists of hard dojil ware (stoneware) and soft yeonjil ware. Dojil ware’s hardness and grayish-blue color is a result of being fired in a closed tunnel kiln at a temperature of over 1,000℃. Yeonjil ware, on the other hand, was fired at low temperatures in an open pit kiln, resulting in its soft and highly porous vessel walls and red color. Dojil ware was mainly used for storage or for ceremonial or decorative purposes, whereas yeonjil ware mainly consisted of everyday vessels.

Dojil ware demonstrating Gaya characteristics is extremely varied in nature, and distributed over a wide area extending from the region of South Gyeongsang Province south of Gayasan Mountain to the eastern part of the Honam region. Distinct differences in terms of form and decoration can be observed between the pottery used by the different polities of Gaya but what they share in common is the sophisticated beauty of their flowing lines. Gaya pottery production technology also had an influence on the beginning of sueki ware production in ancient Japan.

- Section 37What did the People of Gaya Eat?

- Section 38Years of Hard Work Leads to Success in Firing Hard Pottery

- Section 38Years of Hard Work Leads to Success in Firing Hard Pottery

- Section 39Observing, Hearing and Experiencing Pottery

- Section 40Characters and Symbols Used by the People of Gaya

- Section 41Diverse Forms and Patterns

- Section 42Separately and Together

- Section 43Praying for Prosperity and Peace Using Figurative Pottery

- Section 44Appeasing the Spirits with Ernest Offerings

- Section 45Foreign Traces Found at Gaya Sites

It is recorded in the Garakguk-gi Chronicle of Samguk Yusa (Memorabilia of the Three Kingdoms) that the people of Gaya “sowed the fields and ate grains.” The passage that “the soil is fertile and suitable for growing the five grains and rice” which appears in the chapter on the Han (韓) People, Sanguozhi Weishu Dongyizhuan (Records of the Three Kingdoms, Book of Wei, Biography of the Eastern Barbarians) suggests that farming was actively carried out in Gaya. Historical and archaeological records indicate that the five grains (rice, barley, foxtail millet, broomtail millet, and legumes) were consumed, as were vegetables and fruits such as peaches.

In addition, livestock (such as cows and pigs), wild boar and deer, chestnuts and acorns gathered from the woods, and freshwater and saltwater fish and shellfish were also consumed as important food substances.

Cooking stoves have been found at Gaya dwellings. Historical records describe how the Gaya people worshiped the Kitchen God, which indicates that the kitchen, where fire was kept, was regarded as a sacred place in Gaya society.

-

Funace-shaped Pottery Unknown,

Height: 19.0cm -

Boiling Pot-shaped Pottery Bonghwang-dong, Gimhae,

Height: 28.0cm -

Mounted Dishes Ogok-ri, Haman,

Height: 15.2cm

-

Jar Marisan, Haman,

Height: 55.0cm

Gaya pottery was fired in sealed tunnel kilns. Tunnel kilns could be constructed below ground, by digging tunnels into the hillside, or they could be semi-subterranean, featuring ceilings that were located above ground. Each kiln consisted of a fire box into which fuel was inserted, a firing chamber that contained the pottery, and a chimney through which heat and smoke could escape. Tunnels were located at places where it was easy to obtain large amounts of clay, firewood used as fuel, and water, and where it was also convenient to transport the final products. The representative kiln sites of Gaya have been found at Yeocho-ri (Changnyeong) and Ugeo-ri (Haman). A kiln site that produced Dae Gaya pottery was also excavated at Goryeong.

-

Anvil Used in Pottery Productions Ugeo-ri, Haman,

Length: 11.5cm -

Paddles Sinbang-ri, Changwon ∙ Bonghwang-dong, Gimhae,

Length: 11.5cm

This rattle cup features a section containing clay balls at its base. The clay balls were fired first and then inserted into the vessel that was subsequently fired. The clear sounds made by the clay bells of the rattle bring joy to the listener. Such rattle cups were not merely used to serve liquids but also functioned to enhance flavors by bringing pleasure to the eyes and ears.

Producing clear sounds, the rattle cup is also likely to have been used to ward off evil spirits, as in the case of the shaman’s bells. The charm of the Gaya people, who enjoyed good sounds and flavors, can be gleaned from this artifact.

-

Bell Pottery Marisan, Haman,

Height: 8.0cm -

Bell Pottery Gyeseong, Changnyeong,

Height: 16.0cm

Texts were written on wooden or bamboo slips prior to the invention of paper. The discovery of a brush and a hand knife that was used to erase writing at the site of Daho-ri (Changwon) indicates that writing was practiced as early as the 1st century BCE. For Byeonhan, writing would have been required in order to carry out trade with their Chinese counterparts.

The representative inscriptions found on Gaya artifacts are as follow: 西口宮 (“Seogugung”, meaning “Seogu palace”) inscribed on a bronze tripod cauldron from Yangdong-ri (Gimhae); 下部思利利 (“Habusariri” meaning “the lower bu of Sariri”) inscribed on pottery vessel from Jeopo-ri (Hapcheon); 上部先人 (“Sangbuseonin” meaning “a person of the upper bu) inscribed on a sword from Gyo-dong (Changnyeong); 大王 (“Daewang” meaning “great king”) inscribed on a long-necked jar of unknown context; and 二得知 (“Yideukji” believed to be a name) inscribed on a pottery vessel from Hacheon-ri (Sancheong). These inscriptions comprise important data that can help shed light on the nature of Gaya politics and society.

-

Bowl with Two Lugs Inscription of "二得知" Hachon-ri, Sancheong,

Height: 8.7cm -

Bowl with Two Lugs Inscription of "二得知" Hachon-ri, Sancheong,

Height: 8.7cm -

Long-necked Jar with Horse Design Seokdong, Changwon,

Height: 28.5cm

Mounted dishes, which are known as “tou (豆)” in China, were often used as ritual vessels. Consisting of a shallow bowl-like dish placed upon a high mount, they are the most frequently found type of Gaya pottery. The different regional types of Gaya pottery can be ascertained from the shapes of the perforations featured on the mounts or by the patterns used to decorate the vessels.

Gaya mounted dishes are diverse in shape. Those similar to present-day mugs, which have a large handle affixed to a cylindrical body, are referred to as cup-shaped pottery. The mounted cup consists of a wide-mouthed cup placed upon a mount and is characterized by a large handle that extends from the mount to the cup. Some mounts feature clay pieces and there are also cases in which mounts were attached to small cup-shaped.

-

Cup with Handle Marisan, Haman,

Height: 9.6cm -

Cup with Handle Hwangsa-ri, Haman,

Height: 12.4cm -

Cup with Handle Jisan-dong, Goryeong,

Height: 13.5cm

The kingdoms of Gaya did not come together to form a single state but rather maintained a distinctive culture defined by freedom and co-existence This is well illustrated by the existence of diverse regional pottery types. Their forms are similar but the distinctive styles of each region can clearly be seen.

Different types of pottery were produced according to need, with mounted dishes, long necked-jars, vessel stands, and covered dishes being the representative types that well demonstrate regional diversity. Mounted dishes, in particular, show strong regional characteristics: Garak-guk (Geumgwan Gaya) mounted dishes have outwardly protruding lips, Ara-guk (Ara Gaya) mounted dishes are decorated with flame-shaped perforations, and Goja-guk (So Gaya) mounted dishes feature triangular perforations.

-

Brazier-shaped Pottery Daeseong-dong, Gimhae,

Height: 28.0cm -

Cylinder-shaped Vessel Stand Bangyeje, Hapcheon,

Height: 68.5cm -

Mounted Dishes with Lid Yesu-ri, Sacheon∙Gajwa-dong,Jinju,

Height: 16.0cm(right)

-

Mounted Dish Haman, Dohang-ri,

Height: 19.0cm

Figurative pottery was made in the form of humans, animals, and other objects. The pieces represent animals (such as ducks, deer, and horses) and everyday items (such as houses, boats, carts, and horns, etc.) in a simplified, exaggerated or abstract way. They are hollow and feature holes though which liquids can be poured in or out. They tend to be discovered in tombs or ritual contexts, indicating that the pottery served ritual purposes, imbued with prayers for the deceased’s peaceful rest in the afterlife upon the ascension of his or her soul, rather had being an item used in everyday life.

-

Cart-shaped Pottery Marisan, Haman,

Height: 15.0cm -

Cylinder-shaped Pottery Yangdong-ri, Gimhae,

Height: 12.0cm -

Horn-shaped Cup Unknown,

Height: 21.0cm

The diverse types of objects that were buried as grave goods shed light on many aspects of Gaya culture. Various types of pottery, the most frequently discovered type of grave good, were used in ritual practices commemorating the deceased. The remains of grains, seeds and pits, and animal bones discovered within mountain dishes and jars shed light on the nature of these ritual offerings of food. The food remains that have been discovered within the pottery, therefore, not only provide important information of past diet but also allow us to consider the ideological aspects of food consumption, as well as the time period of the tomb’s use. The meanings associated with the practice of earnestly preparing foods for rituals would not have been dissimilar between the past and present.

Many people from foreign lands settled in Gaya and diverse foreign cultures were introduced as a result of Gaya’s maritime trade relations. Coastal sites located at key spots along the coastal seafaring route have yielded archaeological traces of Wa (Japan) communities, and earrings from Gara-guk (Dae Gaya) have been found at many sites in Japan. This shows that the people of Wa (Japan) and Gaya continuously moved around and lived together. In particular, many examples of ancient Japanese hajiki pottery and sueki pottery have been found at sites southern Korea. Hajiki pottery consists of reddish-brown earthenware jars with vessel mouths that sharply protrude outwards or featuring semi-circular handles, and the body of hajiki ware mounted dishes are sharply angled outwards around the center. Sueki pottery, which is bluish-gray stoneware fired at very high temperatures that produces a metallic sound when tapped, is known to have become produced under the influence of Gaya pottery.

-

Mounted Dishes Hyeon-dong, Changwon ∙Yongwon, Changwon,

Height: 13.0cm -

Jar with Handle Daeseong-dong, Gimhae,

Height: 21.0cm -

Mounted Dishes Saengcho, Sancheong,

Height: 13.0cm