Lives and Cultures of the People Before Gaya

The diverse cultures of the Gaya people developed in the cradle which was the lower Nak-dong River. Paleolithic people maintained mobile lifestyles in search of food. In the Neolithic Age, people lived in pit houses on riverbanks or coastal locations, obtaining food through fishing, hunting, and gathering. Neolithic people also used ground stone tools and pottery and practiced rudimentary agriculture. Bronze implements, ground stone tools, and plain pottery were used in the Bronze Age. Agriculture, including rice farming in wet paddies, came to be practiced on a wider scale and large villages were established. The construction of enormous dolmens symbolically demonstrates how perceptions of the ‘village community’ had come to be strengthened within the farming societies of the time.

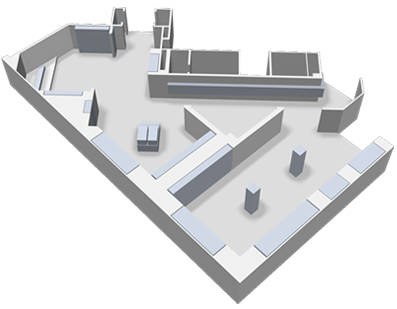

- ●Archaelogical Chronology from Paleolithic to Gaya

- section 1Oldest Traces of Human Activity

- section 2The Oldest Boat from the Korean Peninsula

- section 2Venturing Out into the Rivers and Seas

- section 3Changnyeong Soil Layer Transcription

- section 4Adapting to a New Environment

- section 5Appearance of Pottery

- section 6Neolithic People in Life and Death

- section 7Emergence of Farming Villages

- section 8Bronze Age Utilitarian Items – Tools Made of Stone

- section 9Bronze Age Utilitarian Items – Plain Pottery

- section 10Red Burnished Pottery and Pottery with Eggplant Designs

- section 10Red Burnished Potteries

- section 11Dolmens – Monuments of Farming Society

- section 11Polished Stone Dagger

Paleolithic people chipped flakes off stones to make the tools needed for hunting and gathering. These chipped stone tools were suited for various activities, such as stabbing, cutting, digging or scraping, and pounding. The tools were usually made with stones that could easily be found in the vicinity but at times, certain types of stones were deliberately chosen in order to serve specialized functions. The large stone tools of the earlier period were gradually reduced in size and became more elaborate over time.

-

Tanged Point Gorye-ri, Miryang,

Length: 8.5cm -

Micro-blade Cheonhwangjae, Miryang,

Length: 2.2cm -

Micro-blades Cheonhwangjae, Miryang,

Length: 2.4cm(Left)

Bibong-ri, Changnyeong, Length: 178.4cm

Prehistoric Boat(Restored Version)

Neolithic people undertook exchanges with neighboring regions to gain resources that could not be easily obtained locally. Obsidian stone tools and Japanese Jomon pottery discovered at sites located along Korea’s southeastern coastline reveal how the communities of this region maintained exchange relations with the communities of the Kyushu region of the Japanese Archipelago. A typical exchange good that originated from the Korean Peninsula was the bracelet made using the shells of the Glycymeris albolineata clam.

-

Obsidian Arrowhead Dongsam-dong, Busan,

Length: 4.3cm -

Obsidian Flakes Hwamok-dong, Gimhae,

Length: 3.1cm(Right) -

Japan Jomon Pottery Dongsam-dong, Busan,

Height: 11.1cm

Bibong-ri, Changnyeong

Around 10,000 years ago, the natural environment of the Korean Peninsula came to resemble that of the present day due to a gradual increase in the earth’s temperature. People used bows and arrows to hunt fast animals, such as deer and wild boars, that lived in warm climates. At riverine and coastal locations fishing hooks, harpoons, and nets made of bone or stone were used to acquire a wide range of food resources. Net bags, which were used to store food that had been hunted and gathered, have also been found. Stone plowshares and hoes used to till the soil were discovered, indicating that the first steps towards farming had been taken.

-

Potsherd with Incised Wild Boar Bibong-ri, Changnyeong,

Length:17.5cm -

Bone of Eared Seal Dongsam-dong, Busan,

Length:14.9cm -

Plowshare Sinan, Miryang,

Length:15.1cm

Upon discovering that the application of heat can harden clay, Neolithic people began to make pottery. With the invention of pottery, it became easier to store and transport food that had been obtained using much effort, and cooking methods also changed. Pottery, which appeared around 10,000 years ago, was produced in various shapes and decorated using various patterns depending on the region and period. Of the diverse decorative methods that were used, including the use of raised designs or impressed patterns, the use of comb patterns (rendered using a tool for incisions) is the most widely known.

-

Small Pottery Dongsam-dong, Busan,

Height: 12.2cm -

Red Painted Pottery Dongsam-dong, Busan,

Height: 16.7cm -

Small Pottery Dongsam-dong, Busan,

Height: 6.4cm

Various types of burials were used during the Neolithic Age. The most common method was to bury the deceased in a pit, but in some cases, the deceased was placed in a cave or only the de-fleshed bones were collected. The deceased individual was adorned with bracelets or anklets made of shells or animal bones, and pottery was placed nearby. A Neolithic Age cemetery was discovered on Gadeok Island in Busan, yielding the remains of at least 48 individuals, making it the largest of its kind identified thus far in Korea. Unlike other regions where the deceased was placed in a flat horizontal position, the individuals buried at this cemetery were mainly placed in a crouched position, like a baby in its mother’s womb.

-

Jade Yeondaedo, Tongyeong,

Diameter: 1.8cm -

Anklet Yeondaedo, Tongyeong,

Length: 1.8~3.0cm -

Shell Bracelet Suga-ri, Gimhae,

Length: 8.3cm

The practice of rice farming was firmly established in the Bronze Age. Unlike the small-scale cultivation of grains such as foxtail and broomcorn millets that took place during the Neolithic Age, rice farming required a large labor force, leading to the emergence of large-scale villages. A typical Bronze Age village scene consisted of pit houses, dry crop fields and rice paddies, and ditches or fences surrounding the entire village. The establishment of farming as the most important subsistence strategy also led to the development of farming tools used to work and harvest the fields.

-

Petroglyph Sinan, Miryang,

Height: 28cm -

Semilunar Stone Knife Banggi-ri, Ulsan,

Length:13.8cm(Right) -

Stone Sickle Seobu-dong, Ulsan,

Length: 21.6cm

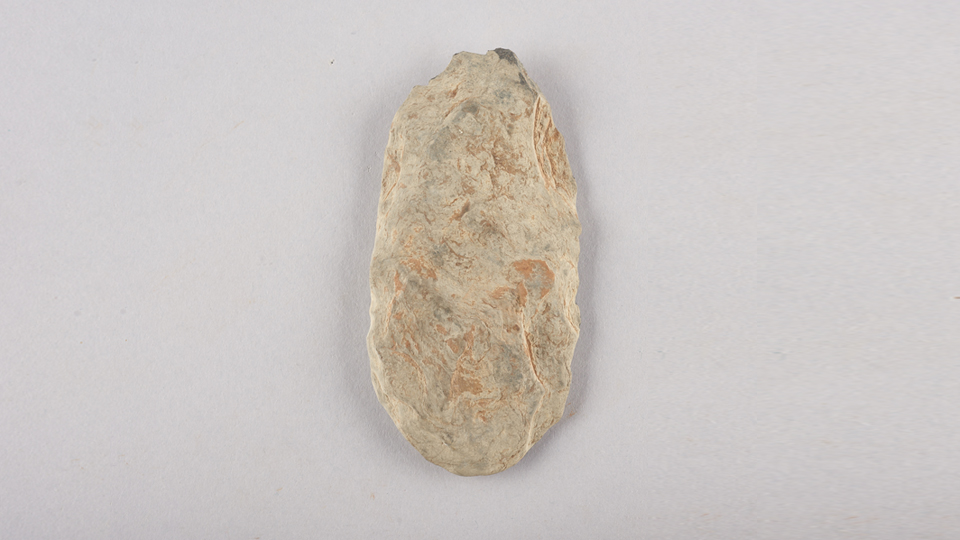

Although farming was established as the key subsistence strategy during the Bronze Age, hunting and fishing were also maintained as important methods of food procurement. This is evidenced by the presence of stone arrowheads, stone spearheads, and net weights. Wood was also a key material for the production of various household tools. Accordingly, a wide range of woodworking tools were also developed in order to process wood with precision, such as bifacial axes, adzes, planes, and chisels. Stone tools were also used to polish jade beads and make necklaces with brilliant colors.

-

Discoidal Stone Axe Sinhwa-ri, Ulsan,

Diameter: 8.7cm -

Fishing Net-sinkers Eobang-dong, Gimhae,

Length: 5.5cm(each) -

Stone Knife Seobu-dong, Ulsan,

Length: 20.9cm

Bronze Age people used plain pottery with surfaces that were generally leundecorated, except for some simple patterns consisting of short lines or holes that were rendered near the vessel’s mouth. Vessels were produced in various shapes according to their intended use, including beakers, bowls, plates, jars, and pots, which were generally flat-bottomed. As in the case of Neolithic comb pattern pottery, different variations of plain pottery were used, according to region and period.

-

Plain Coarse Pottery(Bowl) Daepyeong-ri, Jinju,

Height: 47.3cm -

Plain Coarse Pottery(Dish) Daepyeong-ri, Jinju,

Height: 7cm -

Plain Coarse Pottery(Jar) Sangchon-ri, Jinju,

Height: 36.3cm

Red burnished pottery and pottery with eggplant designs were special types of Bronze Age vessels that required great effort in their production. The red pigment was mixed and rubbed onto the vessel surface to create a shine, or black eggplant patterns were expressed uniquely. Due to the use of high-quality base clay and the application of detailed production techniques, these vessels have a sophisticated appearance, unlike crude utilitarian wares. The vessels were treated as precious items and used as grave goods.

-

Red Burnished Pottery Daepyeong-ri, Jinju,

Height: 24cm -

Red Burnished Pottery Bongnim-dong, Changwon,

Height: 12cm -

Eggplant-decorated Pottery Daepyeong-ri, Jinju,

Height: 23cm

-

Red Burnished Pottery Daepyeong-ri, Jinju,

Height: 8.1cm -

Red Burnished Pottery Mugye-ri, Gimhae,

Height: 11.3cm

Social cohesion and communal labor at the village level (involving practices such as watering the fields, sowing seeds, and harvesting) were of key importance in farming societies. The development of agriculture gave rise to various conflicts both within and outside the community, and the role and authority of those who mediated such conflicts gradually increased. This phenomenon is symbolized by the stone daggers and stone arrowheads placed in huge dolmens. In some cases, the stone daggers and stone arrowheads were of exaggerated size and shape, and this lack of practicality indicates that they were more than just simple tools.

-

Polished Stone Dagger with Hilt Goejeong-dong, Busan,

Length: 25.3cm -

Polished Stone Dagger with Banded Hilt Jeonsapo-ri, Miryang,

Length: 26.9cm -

Polished Stone Arrowhead Geumpo-ri, Miryang,

Length: 17.5cm

Probably Gimhae, Length: 51.5cm